Balancing foreign investment and domestic industry needs

Turkey is on its way to becoming a supply chain hub for the European energy transition.

Turkey is on its way to becoming a supply chain hub for the European energy transition. Increased government attention to renewable energy policy has bolstered financial stability, attracted foreign investment, and allowed clean capacity to flourish. At the same time, Turkey balances its policy environment with enough local content requirements to incentivize domestic manufacturing.

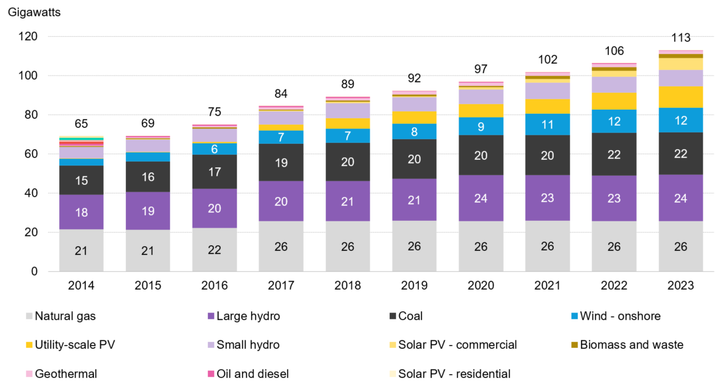

• Renewable energy is flourishing in Turkey. Thanks to a policy environment that has successfully attracted large renewable energy investments, renewables made up more than half of the country’s capacity at the end of 2023.

• Turkey has also implemented ambitious energy transition goals. To reach these goals, however, Turkey must pick up the pace of clean power build and unclog existing bottlenecks. Most of Turkey’s inhabitants are in the western portion of the country, while generation is concentrated in the central and eastern areas. Improved transmission lines are thus urgently needed – as is more investment in new grid infrastructure – to connect the middle of the country to demand centers.

• A diverse array of policies has been designed to tackle challenges with transmission infrastructure and financial instability. Turkey’s schemes for feed-in-tariffs, auctions and renewables certificates have all been revamped in the last five years, minimizing currency risk and upping investment appeal. Local content requirements have also given domestic manufacturing a boost.

• The Turkish energy sector has struggled with both financial and regulatory challenges over the past decade. In response, the government has developed and begun implementing tools for making investments feel more secure. This could provide a foundation for getting further energy transition opportunities – including green hydrogen, electric vehicles and a cohesive carbon market trading system – into gear.

Figure 1: Installed capacity in Turkey

Source: BloombergNEF. Note: PV refers to solar photovoltaic. ‘Other - fossil’ accounts for plants that use more than one fuel or fuels other than coal, oil and gas.

1. Low-carbon strategy

Turkey published its first Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) in 2023, pledging to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions by 41% by 2030. This joins the National Energy Plan, published the year before, which targets 24.5 gigawatts (GW) of onshore wind, 5GW of offshore wind and 59.9GW of solar by 2035. Turkey has also set a target of 23.7% of primary energy consumption from renewable sources by 2035 and a net-zero target for 2053.

While this target is ambitious, it lacks key specifics for selected sectors. This could be a stumbling block for both internal and external stakeholders, as sectoral emissions and scenario forecasts are important factors to take into account when making investment decisions.

2. Power

2.1. Energy transition progress

Renewable energy is flourishing in Turkey. The country now has 12 gigawatts (GW) of wind and 17GW of solar, of which 5GW and 11GW were added, respectively, in just the last five years. Recent governmental incentives, including the new Yekdem feed-in tariff scheme, the dollar-based Yeka auction scheme, and market liberalization efforts such as corporate power purchase agreements (PPAs), have set Turkey on a stronger path toward achieving its targets. A gradual shift since the early 2000s to an 80% private sector structure has bolstered renewables’ share of installed capacity. Renewables now account for 57% of the country’s capacity as of 2023, and a more secure investment environment has attracted more than $24 billion in renewable energy investments from 2019 to 2023.

However, to reach the capacity target specified in the national energy plan – which adds nearly 90GW of renewables by 2035 – Turkey must pick up the pace. As of now, it has no offshore wind capacity and just 29% of the targeted solar capacity. Only onshore wind has crossed the halfway point to the 2035 goal.

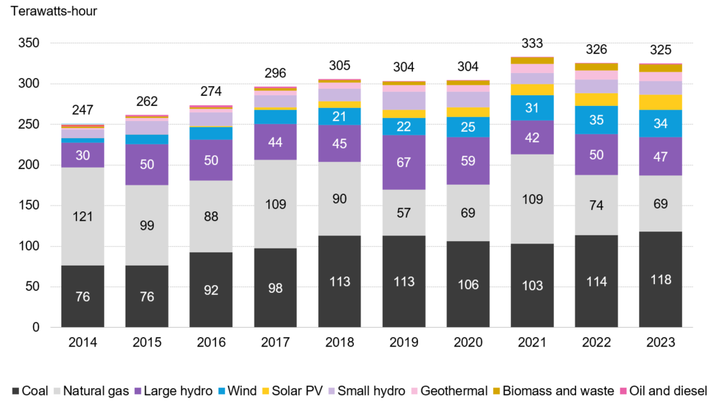

Figure 2: Generation in Turkey

Source: BloombergNEF. Note: PV refers to solar photovoltaic.

The 2022 National Energy Plan not only highlights renewables goals but also specifies capacity targets for all types of power sources, aiming for a total combined capacity of 189.7GW from power plants. Currently, approximately 60% of Turkey’s energy consumption relies on fossil fuels, primarily coal and imported natural gas for power plants. There are ongoing discussions about domestic natural gas production from the Black Sea, and nuclear energy could soon start to play a role in the energy mix. Additionally, rooftop solar installations, hybrid systems and internal consumption strategies are gaining traction.

2.2. Power policy

Turkey’s renewable energy policies are designed to attract foreign investment while fostering domestic manufacturing growth. The Renewable Energy Support Scheme (Yekdem), revamped in 2021, guarantees fixed tariffs with additional strong incentives for using domestically produced equipment, highlighting the country’s protectionist approach; it has also effectively minimized investor currency risk through its linkage with foreign exchange rates and inflation. Adjustments in its pricing mechanism and monthly reviews are designed to align the tariffs with economic indicators, maintaining investment appeal.

The auction-based Renewable Energy Resource Area, or YEKA, scheme allocates government-designated land for renewable projects. This, too, includes local content requirements to boost domestic manufacturing. Since 2017, YEKA schemes have fallen into two categories: YEKA-Ges (solar auctions) and YEKA-Res (wind auctions).

The first auctions were in dollars. In 2020, they shifted to local currency, but concern around the stability of the Turkish lira cut into investor participation. The Ministry of Energy (MoE) has thus announced a new, dollar-based YEKA auction for both wind and solar.

The distributed energy schemes are more focused on industrial and commercial sectors. The net-metering policy, for example, is widespread in these sectors, allowing customers with rooftop solar panels to sell surplus electricity back into the grid. However, residential customers’ adoption of such policies remains limited due to both bureaucratic challenges and the fact that many customers live in apartment buildings, which makes calculating these electricity sales a challenge.

New permitting rules for co-located projects are also sparking developers’ interest. In November 2022, Turkey made it possible for energy storage developers to get a license for a co-located solar or wind plant of the same capacity without going through an arduous request process for a separate permit. Pre-license applications for this program surpassed 200GW, which is more than the country’s total installed capacity.

Turkey also boasts a well established renewable trade market supported by the company Energy Exchange Istanbul (Exist) – or Enerji Piyasaları İşletme A.Ş. (EPİAŞ) by its Turkish name – which certifies production from solar, hydro, biomass, wind and geothermal energy in the renewable energy certificate scheme, known as YEK-G. The certificates are aligned with EU standards to promote tax-exemption export opportunities. These measures are further shaped by external factors like the European Green Deal and Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) regulations, which put pressure on Turkish exporters to enhance decarbonization efforts.

Turkey employs multiple tools to support its renewable energy industry and foster local manufacturing. Key policy measures include very strict local content mandates in YEKA auctions (only big domestic manufacturers such as Kalyon may build the solar cells), higher rates with a five-year bonus incentive for domestic equipment use in Yekdem, and alignment between YEK-G and the EU standards, which supports exporters through a tax exemption solution and ensuring compliance with the European Green Deal and CBAM. This last item is crucial, as CBAM’s emissions regulations now impact goods like iron, steel and cement exported to the EU.

Since 2016, Turkey has implemented additional local content requirements for the state aid provided to renewables projects. Subsidies offered by the Investment Incentive System support a large share of energy generation projects in the country – including more than 17,000 solar projects from 2016 to July 2024, at an estimated cost of nearly $1.2 trillion Turkish lira ($34 billion). Yet these subsidies exclude the cost of solar panel carrier construction systems imported from abroad and solar panels produced without using domestically produced solar cells from government funding offered to the generation project. In 2024, the schemes' local content requirements were expanded to impact wind projects. The cost of imported generators and nacelles with generators produced abroad are now excluded from government funding.

2.3. Power sector structure: Grid constraint affects prices and costs

Turkey struggles with a geographic mismatch between population and generation. Most of Turkey’s inhabitants are in the western portion of the country, while generation is concentrated in the central and eastern regions. For instance, there is a hub of solar plants located in Konya, in the center of Turkey, where there is limited demand. Improved transmission lines are thus urgently needed – as is more investment in new grid infrastructure – to connect the middle of the country to demand centers.

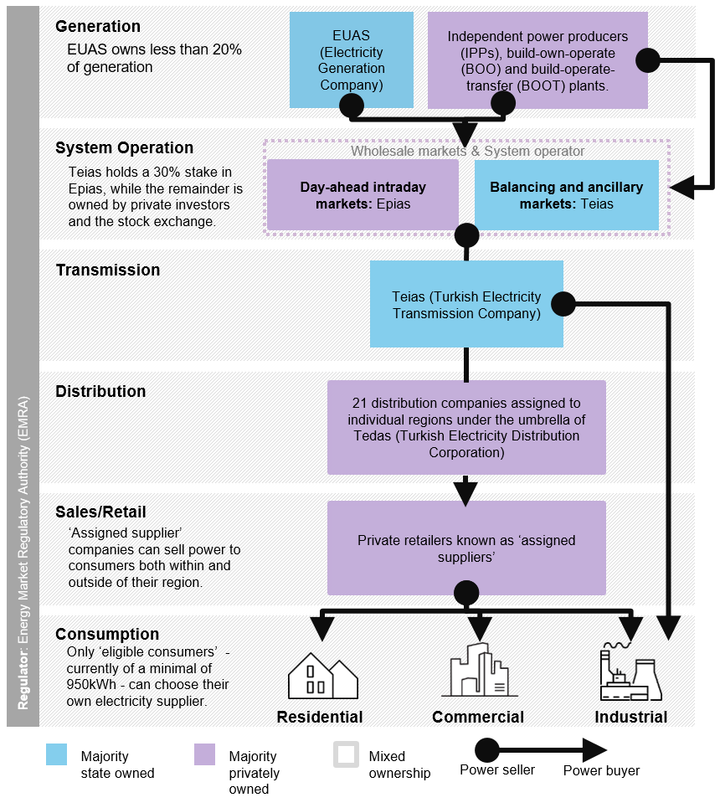

Currently, state-owned Electricity Generation Company (in Turkish: Elektrik Üretim A.Ş., or EUAS) owns a bit more than 20% of licensed electricity distribution in Turkey. The rest is split between BOOT plants (which stands for (build, own, operate, transfer), free manufacturing companies and plants with transferred operating rights. To deal with this geographical issue, small-scale solar projects are incentivized since they require less available space and can be closer to consumption points. The unlicensed market for corporate solar PPAs, which is driven mostly by self-consumption assets, attracts many players that want to reduce electricity prices by untangling them from transmission costs. Since 2018, unlicensed power plants have led to high rates of solar and hydro development across the eastern portion of the country.

The right to choose one’s own supplier is available only to large customers that are directly connected to the transmission system, such as industrial zones and consumers with annual consumption of over 4 megawatt-hours (MWh). But this is changing: the eligibility criteria are being reduced by the Energy Market Regulatory Authority (EMRA) to increase the number of users who can freely choose their supplier, and prices for manufacturers generating electricity for their own consumption are generally lower and more transparent.

3. Barriers and opportunities

3.1. Financial and political instability

Over the last decade, the Turkish energy sector has struggled with an array of financial and regulatory challenges. First, national energy companies have been saddled with dollar-denominated debt, and the depreciation of the lira has made servicing these loans an increasing burden. Second, there is a lack of clear eligibility criteria for generation licenses, especially for solar and wind plants. And the absence of long-term market visibility leads to challenges securing project financing. Loans often require substantial equity investment, which directly affects domestic investors.

In the past couple of years, the market has become more stable, and the government has developed tools for securing investors (see more in the Policy section above). Institutionally, the current administration has gained the trust of international players, and the central bank tends toward orthodox policies favored by major financial entities such as the International Finance Corporation (IFC), leading to increased lending prospects. In line with these scenarios, there is hope that hefty subsidies for natural gas and electricity for residential uses – which have kept prices down – use will be phased out in the coming years, paving the way for a more resilient, competitive and transparent energy sector.

Figure 3: Power market diagram

Source: BloombergNEF. Note: kWh refers to kilowatt-hours.

3.2. Opportunities

Turkey’s grid has a laundry list of needs: grid flexibility, dynamic pricing, regional targets and coordination mechanisms. Besides that, challenges due to lack of information would be improved with digitalization of the transmission system. Yet these challenges also point to significant opportunities.

Turkey may be set to prosper from Europe’s apparent desire to diversify the supply of components needed for the energy transition. Exports to the EU are tariff-free thanks to a free-trade agreement with the bloc signed in 1995, and government policies comprehensively support local manufacturing. The manufacture of clean technology components is among the most prioritized sectors of the Investment Incentive System (Yatırım Teşvik Sistemleri). Clean technologies can receive tax exemptions, tax reductions, financing support, and both land and labor cost support. If picked as a “strategic Investment”, support can be further increased by presidential decision to apply “project-based state aid” (Proje Bazlı Teşvik Sistemi). The volume of available manufacturing subsidy support, however, is hard to track, with potential funding often folded within larger pots. In July 2024, the government announced a further $30 billion in support for high-priority technology areas, including support for the EV, battery, solar and wind sectors.

Turkey is also keen to build out EV manufacturing and uptake. Annual EV sales jumped to 75,000 in 2023, from 9,000 in 2022. Meanwhile, domestic manufacturer Türkiye'nin Otomobili Girişim Grubu (TOGG) began scaling production in 2022. Under this year’s update to public procurement criteria only TOGG vehicles are eligible to be purchased for the 115,000-vehicle government-owned fleet. While state banks are also offering reduced loan rates for consumers to purchase TOGG vehicles, a lack of government purchase support may keep vehicles unaffordable for many and hinder uptake. This may change if Turkey continues to welcome Chinese electric vehicle manufacturers, such as BYD, which produce a wider range of affordable models.

At the beginning of 2023, Turkey published a Hydrogen Strategy Roadmap, outlining the country’s goal of becoming an important player in the hydrogen world, although high costs and the need for technological adaptation in sectors like aluminum, steel and cement remain speed bumps on this road. Companies like Enerjisa Üretim are spearheading hydrogen pilot projects, while BOTAS is working on a project in Konya to integrate hydrogen into natural gas, targeting a blend of 12-15%. Lastly, if the Turkish emissions trading scheme (ETS) syncs with the EU version, it will bolster Turkey’s position as an exporter for EU markets. This could apply not only to manufactured goods, but also for energy sources such as gas. Turkey may be rewarded for having its exports subject to carbon pricing: its steel is notably produced at a Scope 1 emissions intensity well below the global average.

NetZero Pathfinders

For more information on best practices and climate action, explore the NetZero Pathfinders project by BloombergNEF.