Political instability and a power market monopoly hamstring net-zero goals

Huge clean power potential remains hamstrung by political instability and a power market monopoly.

Tunisia is locationally privileged, with both the natural resources necessary to build ample renewable energy capacity and easy accessibility to European markets. Yet a perpetually changing administration, an opaque policy regime, and a market monopoly on power are challenging the country’s ability to reach its climate goals.

- Under its long-term decarbonization strategy, the government has pledged to reduce emission by as much as 45% come 2030, compared with 2010 levels. To enable this, Tunisia plans to increase renewable energy buildout, prioritize energy efficiency in both industry and transportation, and further strengthen its grid infrastructure.

- Meeting this target requires significant capital – to the tune of $14.4 billion over 2021-2030, according to the Nationally Determined Contribution submitted by the Tunisian government. Only 23% of this total is estimated to be financed by Tunisia alone, with the remaining $11.1 billion required to come from international contributions.

- Approximately 97% of Tunisia’s electricity is currently generated from fossil fuels. Nearly half of it is met through gas imports (mainly from Algeria). Tunisia has enacted a long-term target of 35% renewable electricity generation by 2035. Reaching that goal will require more than 3.5 gigawatts of clean energy capacity, in the form of solar, wind and biomass.

- No grid connection clause was written into Tunisia’s original renewable energy target, legislated in 2015. This means that projects that have won tenders and finished construction cannot connect to the grid. The state-owned Société Tunisienne de l’Electricté et du Gaz controls the power market and is against privatization. This elevates the risk profiles of these projects and makes it difficult to mobilize capital, both local and international, into the market.

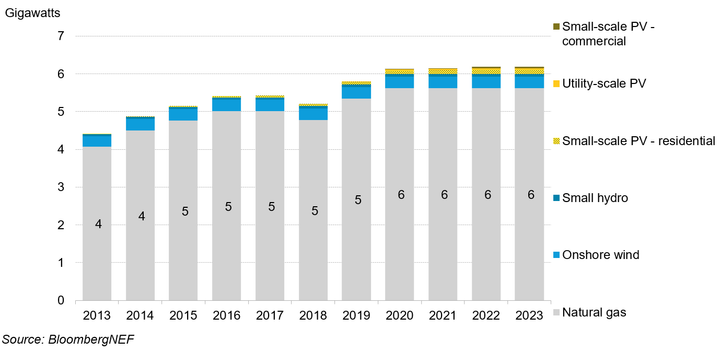

Figure 1: Installed grid-connected power capacity that supplies Tunisia

1. Low-carbon strategy

In October 2016, Tunisia submitted its Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC), a non-binding plan to achieve the goals set out in the 2015 Paris Agreement. In the NDC, the country pledged to reduce emissions by 45% come 2030, compared with 2010 levels. If successful, this will impose a downwards trajectory in terms of absolute emissions, meaning emissions will continue to fall even after 2030, and in 2022, Tunisia submitted a long term strategy to reach net zero by 2050.

Meeting just the 2030 target requires significant capital. The government has estimated that it will take $14.4 billion over 2021-2030. Less than a quarter of the total is estimated to be financed by Tunisia alone; the remainder will need to come from international contributions. The key target areas in the NDC include increasing renewable build out, prioritizing energy efficiency in both industry and transportation and further strengthening grid infrastructure.

2. Power

2.1. Power policy

Approximately 97% of Tunisia’s electricity is currently generated from fossil fuels, mainly natural gas, around 47% of which is met through mainly Algerian gas imports. Tunisia enacted a long-term target of 35% renewable electricity generation by 2035. That would require hitting intermediate goalposts of building 1806 megawatts (MW) by 2022 and 3815MW of power generation by 2030; the first of these was already missed.

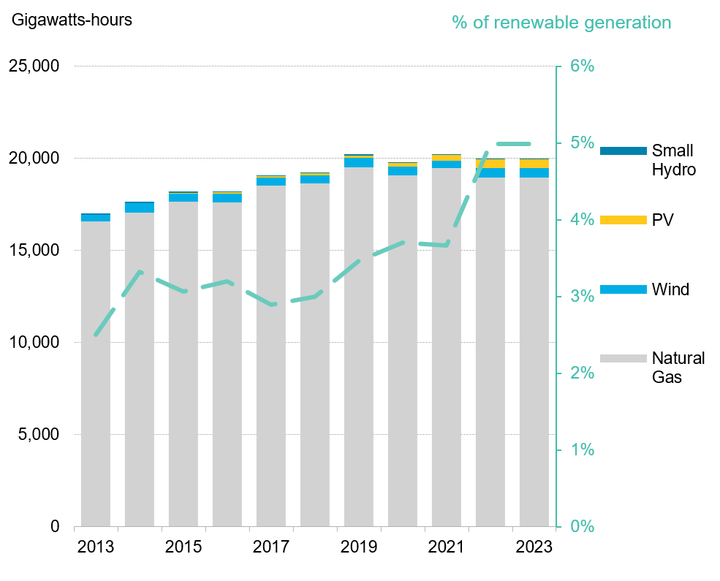

But Tunisia’s government has done little by way of incentives and policy to achieve this level of renewable penetration. There is currently no fossil-fuel phase-out policy in place to kickstart the transition, and auctions for renewables are only just beginning to ramp up (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Domestic grid-connected electricity generation in Tunisia

Solar and wind

Tunisia launched a series of solar and wind tenders in 2017. The first, held in November 2017 under the Authorization Regime, contracted 64MW of solar photovoltaic (PV) capacity, split among six 10MW plants and four 1MW projects. This capacity has since been commissioned and has been followed by auctions for a further 70MW of PV awarded in 2020. As for the Concession’s Regime, the first 500MW was awarded to five solar PV projects in 2019, while 300MW of wind farms will be installed in five regions identified by the government.

Overview of Tunisian regimes for renewable energy

There are three regimes in Tunisia designed to increase the penetration of renewables in the country’s energy mix. The regimes facilitate tenders for renewable power production and the subsequent sale of said power to STEG.

Concessions Regime

- Applicable to large-scale production projects for export.

- Projects must be above 10MW of installed capacity for solar PV, 30MW for wind and 15MW for biomass.

- Ministry of Energy issues a public call for tenders in which the winners then sign concessions with the Ministry

Authorization Regime

- Applicable to projects below the Concessions Regime limits and/or are only for Tunisian consumption

- Winners will sign agreements with the Ministry of Energy.

Self-generation Regime

- Captive power projects

- Depending on project volage, developers may be required to seek approval from STEG or from the Ministry of Energy, Mines, and Renewable Energy.

A further 120MW of wind has been announced under the Authorization Regime, and 2,000MW of solar and wind auctions are in currently in motion with the first rounds of applications closing in 2023. In October of this year, the government launched the final tender rounds for the construction of several large-scale PV projects to total 200MW of capacity. Applications are being accepted until January 2025.

Yet there’s a major speed bump to all this growth: permitting delays have meant that auction winners from 2019 have not yet begun construction on their projects.

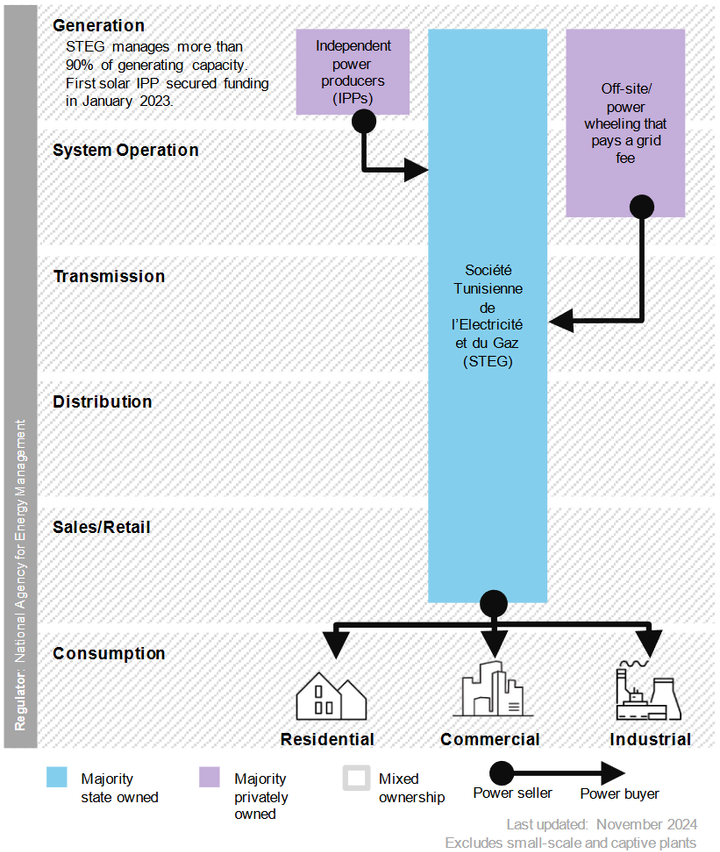

Figure 3: Tunisia power market structure

Hydrogen

Since solar and wind have proven difficult to get going, Tunisia has recently begun moving its clean-power eggs into the hydrogen basket. It released a deployment road map in June targeting 1.1 million metric tons of green hydrogen by 2035 and 8.3 million metric tons of the molecule come 2050. There are currently no incentives for the buildout of said hydrogen and no hydrogen offtake domestically located, but the roadmap suggests an imminent development of a fiscal framework, dedicated to attracting investments into the budding sector.

2.2. Power market

Tunisia’s state utility, the Société Tunisienne de l’Electricté et du Gaz , or STEG, owns a majority of the generation, as well as the grid and retail electricity sectors in their entirety. The company controls 95% of the country’s installed production capacity, and produces around 84% of its electricity. The rest is supplied via imports from Libya and Algeria, and by Tunisia’s only independent power producer, Carthage Power Company. Carthage’s 471MW combined-cycle power plant ended a 20-year PPA with STEG, handing the plant fully over to the state enterprise. STEG is now the only utility that can sell power, granting them a monopoly over the entire energy sector (Figure 3).

2.3. Doing business and barriers

Tunisia is locationally privileged. Its abundant solar and wind, and its proximity to Italy – the two countries are separated by a sea channel shallow enough to allowing bilateral pipeline and cable access – could enable not only an enormous buildout of renewable energy resources but also easy access to European markets. Yet political instability in the form of a perpetually changing administration, opaque policy regime, and STEG’s reluctance to forfeit its monopoly are derailing the country’s ability to reach its climate goals.

Tunisia implemented climate policy and regulation in 2015, but little progress has been made since. Ironically, permitting for solar projects has actually become more difficult as a result of these laws. No grid connection clause was written into the original legislation, meaning projects that have won tenders and finished construction struggle to connect to the grid. Permitting challenges for both solar and wind are compounded by the fact that a successful project must obtain permits from 15 separate government entities. And the Minister of Energy has also been replaced, on average, every eight months for the last eight years.

The makes it difficult not only to render these projects bankable but also to mobilize capital into the market. And many banks – both inside Tunisia and elsewhere – lack expertise on financing renewables projects.

Fortunately, this may now be changing. The government has begun to intervene to allow some of these projects to connect to the grid, although to date just two of the 15 projects awarded tenders have received a green light. And the Ministry is looking to streamline the permitting process to get projects over the line.

NetZero Pathfinders

For more information on best practices and climate action, explore the NetZero Pathfinders project by BloombergNEF.