Following an Orderly Transition to build a greener grid and become a regional strong force in hydrogen production

Ambitious targets, ongoing challenges

The Sultanate of Oman sits on significant solar, wind and hydrogen resources that could place it at forefront of the energy transition. Recognizing this strength, Oman has set ambitious decarbonization targets, particularly in the power, hydrogen and transport sectors. Yet ongoing challenges in infrastructure design and consumer behavior could necessitate an overhaul of relevant policies if these targets are to be met.

- Oman is committed to reducing 21% of its emissions by 2030 as part of its Nationally Determined Contribution submitted to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), relative to a business-as-usual scenario, with targets for the power, transport, buildings, oil and gas and carbon removal sectors. The Sultanate estimates that $190 billion of capital investment is required to roll out its transition plan.

- Oman aims for 30% of its installed capacity to come from renewable sources by 2030, up from just 7.2% today. Wind and solar will play a vital role in this scale-up, but while Oman has a robust grid transmission and distribution system between the main cities, it struggles to connect to rural areas where most renewable resources are located.

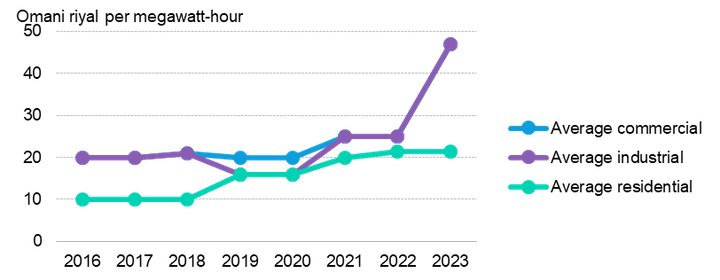

- Oman’s power market is entirely owned and operated by Nama Holding. Nama Power and Water Procurement is the sole power purchaser, and Nama-owned utilities distribute supply electricity to consumers. Commercial and industrial consumers are subject to a cost-reflective tariff, while residentials pay an average of OMR 21.3 per megawatt-hour ($55/MWh).

- Oman has an ambitious hydrogen production goal of 8 million metric tons per annum (Mtpa) by 2050. The Sultanate plans to capitalize on unused land to scale up hydrogen production; land and resources will be allotted by Hydrom, which holds auctions for private project developers. Oman plans to build a separate grid for hydrogen, developed by OQ GN.

- The Ministry of Transport aims to have electric vehicles account for 35% of new registered be EVs by 2030, but less than 1% of passenger vehicle sales were of EVs last year. EV owners are exempt from value-added tax (VAT) and vehicle registration fees, but consumer behavior and preference for internal combustion engine vehicles and relatively cheap fossil fuels are challenging the electrification of transport.

- Despite this comprehensive decarbonization plan, Oman lacks green-friendly infrastructure, requiring a system overhaul and significant investments to bring the plan to fruition. The necessary buildout could be an opportunity for Oman to localize its supply chain, although doing so would likely extend the timeline.

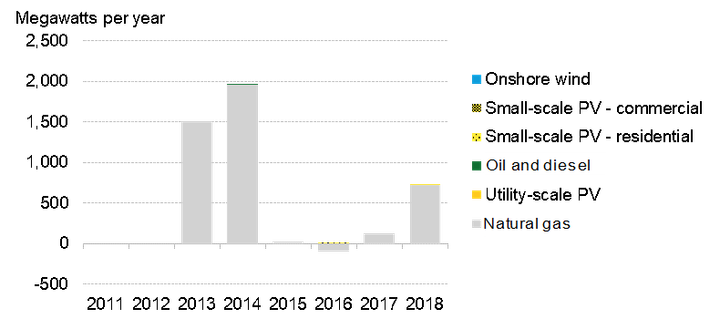

Figure 1: Year-on-year installed capacity in Oman

Low-carbon strategy

Oman submitted its latest Nationally Determined Contributions to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change in November 2023. Oman aims to reduce 21% of emissions by 2030 relative to a business-as-usual scenario, with one-third of that reduction unconditional and other two-thirds linked to climate financing, technology transfers and the operationalization of Article 6 of the Paris Agreement.

Oman’s pathway towards achieving its NDC is its National Strategy for an Orderly Transition to Net Zero, which focuses on several decarbonization levers, including scaling of renewables, energy storage, energy efficiency, sustainable hydrogen and carbon removals. The Orderly Transition states that Oman will require $190 billion of investment to achieve its goals.

There are several actors that are responsible for orchestrating the national net-zero pathway, including the Ministry of Energy, Oman Vision 2040 and the Authority for Public Services Regulation (APSR). Collectively, those government entities are working to decarbonize power, transport, buildings, industry, and oil and gas.

Power

Power policy

The Omani’ government has set a series of increasing targets for the renewable share of power generation: 16% by 2025, 30% by 2030, and 39% by 2040. Separately, the Authority for Public Services Regulation (APSR) set a capacity target of 30% of renewables by 2030.

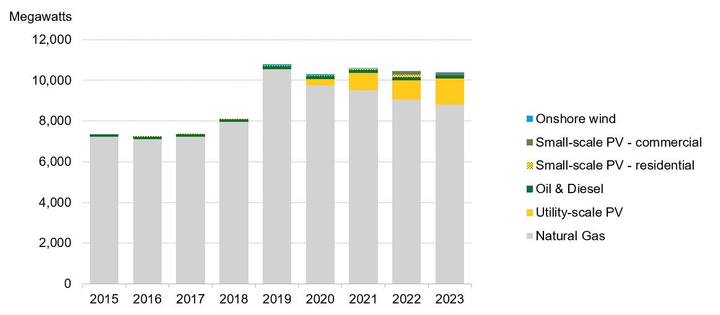

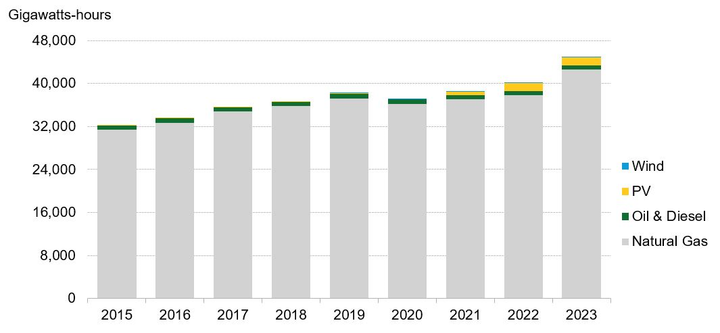

Reaching those goals is going to require a quick scale-up. Only 4% of the 42 gigawatts (GW) generated in Oman in 2023 was from renewable sources. Oman will have to quadruple its renewable energy generation by next year to achieve its national target.

The Orderly Transition prioritizes utility-scale solar and onshore wind arrays to decarbonize the power sector in the short term, while energy storage is part of a longer-term strategy. End-users may also install rooftop solar and benefit from 50% of the connected load via the country’s Sahim scheme, while the rest is fed back to the grid. The Sahim scheme allows end users to install rooftop solar panels and connect to the main grid. A portion of the self-generated solar power will be fed back to the grid and deducted from the user’s energy bill.

Once again, however, there is a big gap between where the country is and where it wants to be, as Oman’s installed capacity is currently just 7% renewable. Natural gas accounts for almost all of the remainder, and oil is 2% of the total.

Figure 2: Oman’s installed capacity, by sector

Figure 3: Oman’s energy generation, by technology

Nama has signed several power purchase agreements (PPAs) with gas, solar and wind plants. Those for solar and wind projects range from 15 to 20 years in duration. According to Nama’s Seven Year Statement, there is currently one utility-scale solar project in operation, Ibri II Solar independent Power Plant, with 500 megawatts (MW) of installed capacity. Nama plans to develop and expand its solar and wind generation with 10 more projects, for a total installed renewable capacity of nearly 4 gigawatts (GW) by 2029.

Oman leans on oil and gas for its economic stability, as gas is its primary energy source and oil is its main export. The country does not plan to phase out fossil fuels entirely from its power sector, and it does not intend to shut down existing power plants prior to their PPA expiry date. To slowly transition the power sector toward cleaner sources of generation, Oman will target renewables for new PPAs and avoid renewing contracts for fossil-fuel power plants.

Power market structure

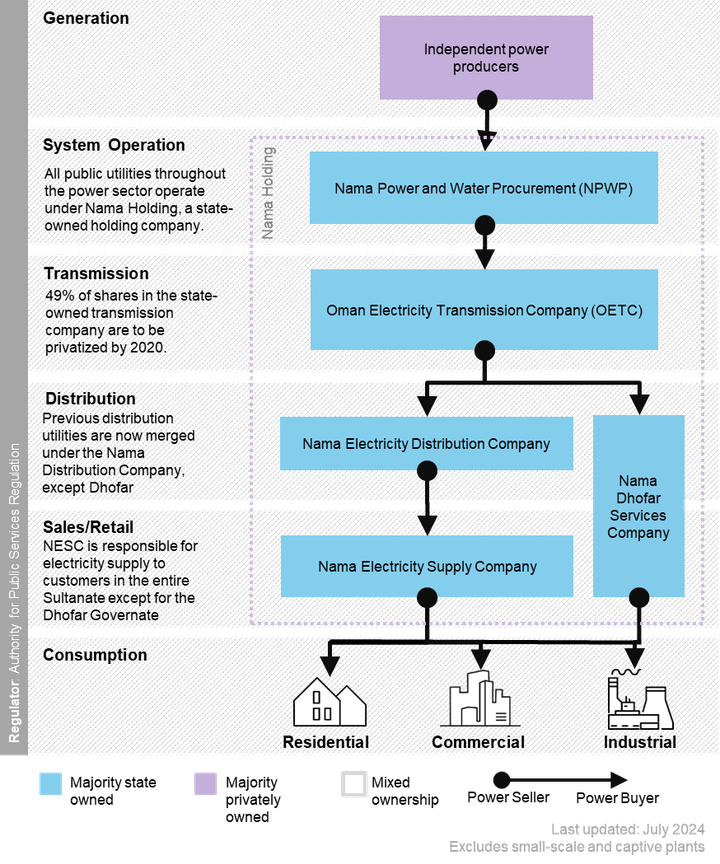

Oman’s power market is mostly government owned and controlled by Nama Holding, a group of companies responsible for power procurement, transmission, distribution and retail in Oman. In turn, Nama Holding is owned by Oman Investment Authority.

Power projects are tendered to independent power producers by Nama Power and Water Procurement (NPWP), which is the only buyer of power and water across Oman’s power systems. The Oman Electricity Transmission Company (OETC) operates the transmission grid for Oman’s power systems.

Oman’s main and largest power system is the Main Interconnected System (MIS), followed by Duqm Power System and Dhofar Power System, plus additional power systems in rural areas. With the exception of Dhofar, all separate distribution companies were merged under the Nama Electricity Distribution Company as part of an effort to improve interconnectivity between power systems. Similarly, Nama Electricity Supply Company supplies power to all customers in the Sultanate except for Dhofar governate. The merger of electricity and supply companies was completed in June 2023.

Figure 4: Oman’s power market structure as of 2024

In January 2022, NPWP launched the region’s first spot market for the wholesale trading of electricity. This will allow captive generators and auto-generators with excess capacity, subject to meeting eligibility conditions, to be able to sell such excess capacity through the spot market. The Omani government expects that the spot market will make investments into projects with significant renewable electricity generation facilities, such as the recently announced green hydrogen projects. The spot market also offers the potential for these projects to realize some level of revenue from the sale of excess capacity. Projects with expired PPAs can also trade power on the spot market.

Large industrials in Oman, such as project developer Petroleum Development Oman (PDO), have their own internal grids and networks.

Power prices

Oman has a 100% electrification rate, according to the World Bank, where the entire population has access to electricity and consumers must be connected to state-owned utility-run grid. Power prices, or tariffs, are set by Authority for Public Services Regulation (APSR) for residential, commercial and industrial consumers. In general, commercial and industrial entities are subject to a cost-reflective tariff (CRT) that accounts for the cost of supplying electricity without government subsifies. As for residentials, they are subject to a fixed-cost tariff that changes seasonally with subsidies. Distributers and grid operators can buy solar-generated electricity from end-users through the Sahim scheme, although this is capped at 50% of the connected load.

For residential consumers, a range of tariffs applies depending on their monthly usage. Users consuming less than 4MWh per month have a tariff of OMR 14/MWh. An account that consumes between 4-6MWh per month pays OMR 18/MWh. And residentials consuming more than 6MWh per month pay a hefty OMR 32/MWh tariff.

Figure 5: Electricity tariffs for different consumers in Oman

As of January 2021, CRT structures apply to commercial and industrial customers whose consumption exceeds 100MWh annually. The tariff consists of four components: hourly energy charges, transmission use of system charge, distribution use of system charge and a supply charge that covers administration costs such as meter reading, billing and collection costs. On average, a CRT is estimated to be OMR 46.88/MWh.

On the consumer end, ASPR is encouraging small-scale solar through the Sahim scheme. Users partaking in Sahim I can benefit from up to 50% of the connected solar load, and any surplus fed into the grid is deducted from their energy bill. The second phase of the scheme will allow private project developers to compete for installing rooftop solar panels on end-users buildings, instead of end-users carrying the installation cost.

Hydrogen

Hydrogen is a focal point of Oman’s energy transition. As such, Oman’s government has set up Hydrom, an entity responsible for operating and scaling up hydrogen production in the Sultanate.

Hydrom is often referred to by the Omani Ministry of Energy and Minerals as an “orchestrator” of hydrogen development in Oman. It is not a project developer. Instead, it is responsible for providing the water, electricity, grid connections and other infrastructure necessary to produce the fuel. Hydrom is building its own grid system to produce 1-1.5 million tons of green hydrogen each yaer by 2030, 3.25-3.75 million by 2040 and 7.5-8.5 by 2050, in accordance with the National Hydrogen Strategy.

As part of Auction Phase A, Hydrom awarded two blocks in Duqm in June 2023, and plans to award three additional blocks by the end of 2024.

One of the barriers to scaling hydrogen production in Oman is a lack of local technology and infrastructure, especially since the country is looking to localize its supply chain. To combat this, the Ministry of Energy and Minerals recognized OQ Group as the “national champion” for hydrogen production and transportation. OQ Alternative Energy is prioritized over foreign project developers when Hydrom assigns projects, and OQ GN will take over the planning and development of Oman’s hydrogen network. This ensures that Oman owns at least a portion of its hydrogen production, rather than outsourcing it entirely.

Energy transition progress: Other sectors

Oman’s energy transition is progressing on multiple fronts, including scaling up renewables, decarbonizing transport and implementing technologies like hydrogen production and carbon capture in industry. Oman’s strategy is intentionally gradual, with relatively slow progress in the early years and then an acceleration as 2050 approaches.

Even so, Oman is currently behind on its first power sector target. As of 2023, 7.2% – or 693 megawatts – of Oman's installed capacity came from renewable energy projects. Oman is looking to grow that figure by an order of magnitude, to 2.6 gigawatts, by next year, which would account for an estimated 16% of total energy production. Such an abrupt scale-up of renewables requires robust energy storage infrastructure to fully utilize renewables that Oman currently lacks, nor has details policies on how to scale up energy storage technologies.

By 2026, Oman aims to operationalized three additional solar projects with a total capacity of 1.5GW, plus five wind projects with a combined 1.1GW capacity. This will put Oman back on track to achieve its installed renewable capacity targets.

To decarbonize the transport sector by mid-century, the Ministry of Transport has laid out ambitious EV sales targets. Under its plan, one-third of new registered vehicles will have a plug by 2030, two-thirds will by 2040, and by 2050, all new car sales will be EVs. To incentivize adoption, EV owners are exempt from VAT and vehicle registration fees. Yet in a country with cheap fossil fuels, that’s still proving to be a hard sell: only 400 passenger EVs were sold last year, less than 1% of total annual passenger vehicle sales of 61,430 vehicles.

On the oil and gas front, Oman has its eyes on decarbonizing the sector’s industrial processes through the use of carbon capture and storage. As discussed in Section 2.1, Oman’s economy is highly dependent on these fossil fuels, leaving the country disinclined to phase them out entirely.

Opportunities and barriers for energy transition

Oman has set up a comprehensive decarbonization strategy to tackle its integrated energy system, which is operated by several stakeholders simultaneously. Theoretically, Oman has infinite access to solar and wind energy, and large plots of unused land that can be utilized for hydrogen production.

However, there is only so much Oman can do without significantly beefing up its infrastructure. To unlock the country’s considerable clean-power potential, Oman’s main grid needs improved interconnection with rural areas, where most renewable resources are located. A new and separate grid will also be required for hydrogen production.

The interconnectedness of Oman’s energy system is both a blessing and a curse. On the one hand, it enables Oman’s energy system to operate in harmony, with multiple stakeholders working in coordination towards shared goals. This is seen in collaborative targets set by the Ministry of Energy and Minerals, APSR, Nama Group, Hydrom, OQ Group and other stakeholders such as the Ministry of Transport. However, bureaucratic inefficiencies could delay the energy transition’s progress.

Oman is also adamant about localizing technology and infrastructure for its energy transition plan, which could delay progress now but reap benefits in the long run. Consumer behavior in Oman is another point of complexity in the country’s the energy transition. In some ways, consumers have little say in this transition. Government-owned entities have a monopoly in multiple sectors, and the energy infrastructure is inflexible, meaning that consumers can neither fully capitalize on self-generation potential nor choose where they purchase electricity.

On the flip side, consumers have shown little desire to embrace the energy transition. Oman’s population is used to driving internal combustion engines, fueled by the lack of an interconnected public transport system and relatively cheap fossil fuels. Stricter policy and sufficient infrastructure will thus both be required to turn drivers away from internal combustion cars and toward EVs and shared transit.

All that said, Oman is well positioned to set up environmental markets in the region. Nama held its first auction round for International Renewable Energy Certificates in 2024 for the Dhofar Wind project. The Sultanate is also considering setting up a carbon market aligning with Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, led by its Environmental Authority.

NetZero Pathfinders

For more information on best practices and climate action, explore the NetZero Pathfinders project by BloombergNEF.