Leaning on coal despite abundant renewable resources.

Though coal is king, Mongolia is blessed with an abundance of natural resources that could make it a renewables powerhouse.

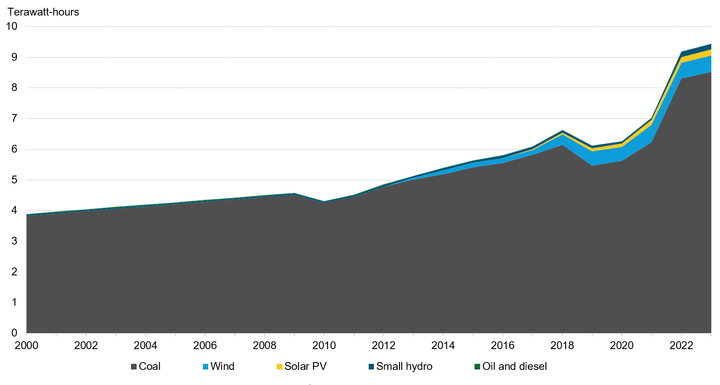

Mongolia has vast potential to decarbonize its power system and host much more renewable energy capacity. The country is blessed with an abundance of land, sunshine and high wind resources. Yet it remains largely reliant on coal generation, which is heavily subsidized, while renewables accounted for less than 10% of the country’s total power generation in 2023.

- The Mongolian government is targeting a 30% share of renewables in its installed power capacity by 2030. It also aspires to be a clean power and hydrogen exporter to other north Asian countries.

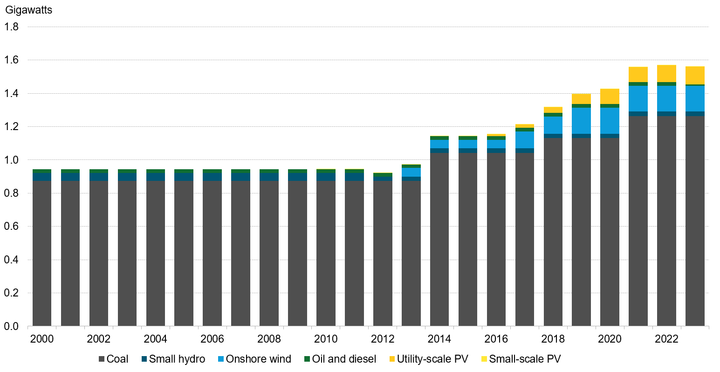

- Mongolia has significant potential to host clean power given the abundance of land and high-quality renewable resources. The Asian Development Bank has estimated that the country’s southern region could host more than a terawatt of solar capacity. But current capacity barely scratches the surface of that figure: 155 megawatts (MW) of onshore wind, 106MW of utility-scale solar, 26MW of hydro capacity, and approximately 3MW of rooftop solar are operational in Mongolia today.

- Building up the country’s renewables won’t be easy. Mongolia has minimal policy support for new renewables, its electricity grid is old and weak and coal generation remains cheap.

- Today, coal is king. Fossil fuel accounted for 90% of power generation in 2023, while generation from solar and wind was less than 8%. No new wind projects have been commissioned since 2018.

Figure 1: Mongolia’s annual electricity generation, by technology

1. Coal: The backbone of Mongolia’s power sector

Although it has no net-zero target, Mongolia has a Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) target to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 22% by 2030 compared to a business-as-usual scenario. If met, the country would see its absolute annual emissions decrease by 16.9 million metric tons of carbon equivalent by the end of the decade.

The country has also set more specific renewable energy targets, under which renewables are to account for 20% of total installed capacity by 2023, and 30% by 2030. Though Mongolia marginally missed its 2023 target – renewables accounted for 19% of total installed capacity last year – its 2030 target could still be in reach. Yet there is a lack of policy, governmental support and necessary mechanisms to help the country develop new clean energy capacity.

Coal is abundant, cheap and the backbone of generation in Mongolia, which has 1.3 gigawatts (GW) of installed coal capacity. The government provides generous subsidies to coal plants, which keeps operational costs of coal generation down. Additionally, the country has no coal phase-out plans, citing energy security as a key priority that could be jeopardized if coal plants retire before cleaner forms of generation come online. In fact, Mongolia is actively adding coal capacity: an additional 300 MW coal power plant is currently under construction to meet growing power demand in the capital, Ulaanbaatar.

2. The uptake of solar and wind installations has stalled

Mongolia faces a plethora of challenges in driving the uptake of clean generation technologies. Grid build-out has been struggling to keep pace with the transition, feed-in tariffs for renewables are too low, coal generation is subsidized and the country currently sees no incentives or government support for new renewables. Mongolia has 26MW of hydro capacity, 155MW of onshore wind, 106MW of utility-scale solar, and approximately 3MW of rooftop solar currently operational today. There has been no wind project commissioned since 2018.

Figure 2: Mongolia’s installed capacity, by technology

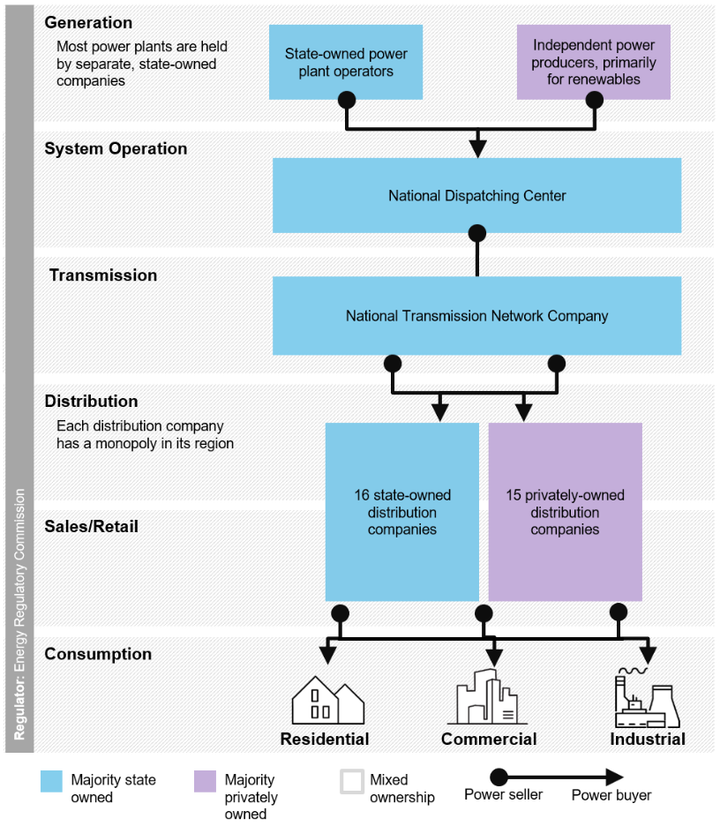

Mongolia's transmission grid, which is aging and weak, acts as a bottleneck for the country's energy transition. As new renewable generators connect to the existing grid infrastructure, they often face significant curtailment due to grid constraints and poor system strength. Building additional transmission in a country so vast with a relatively small population and low demand is costly and challenging. Mongolia may have to rely on global green banks to secure funding for grid expansion if policy support remains inadequate.

Mongolia has set a ceiling on feed-in tariffs – a scheme where renewable developers are awarded a fixed price per unit of generation. These tariffs are capped at $0.085 per kilowatt-hour (KWh) for wind generators, and slightly higher at $0.12/KWh for solar, meaning wind and solar projects will only receive the respective price for their generation. When Mongolia’s feed-in tariffs were first introduced in 2007 for renewable assets, they were more generous, reaching as high as $0.18/KWh for solar and $0.095/KWh for wind projects. The reduction has put a damper on clean energy investment, as developers receive lower returns on their assets than they once did.

Though feed-in tariffs provide revenue certainty for renewable developers, they have posed a significant cost to the government. The cost of power for end users is heavily subsidized and cheap in Mongolia, which means the government cannot look to end users to recoup losses from the feed-in tariffs. At the same time, while the subsidies ensure affordable power for Mongolia’s citizens, they distort market and investment signals. Additionally, the government provides generous subsidies to coal generators through its annual budget, keeping the cost of coal generation low.

All of this has strangled renewables buildout. Feed-in tariffs were caped in 2019. Low tariffs have driven down profits from renewables projects, disappointing investors, and investment in Mongolia’s clean energy sector fell 98% from 2018 to 2020 as a result. Hence, the country sees new coal generation coming online while renewable uptake has stalled.

Mongolia’s ability to meet its clean energy target may thus depend on a new renewable energy deployment strategy, one that ensures there are market incentives to drive further investment into renewable projects.

Figure 3: Mongolia’s power market structure

3. Mongolia’s power system could see big opportunities on the back of greater policy clarity

In order to meet Mongolia’s clean energy targets and broader decarbonization ambitions, the Mongolian government will need to enact robust, coordinated policies to support the greater uptake of renewables and storage technologies, as well as support the country’s grid infrastructure. Displacing fossil-fuel generation with clean power sources will be the largest driver for reducing emissions in the country. To incentivize further adoption of clean power generation, Mongolia could develop a national coal phase-out plan, introduce a support mechanism for new wind and solar projects and accelerate grid expansion.

There are also an array of opportunities and plans on the horizon. If Mongolia’s ability to host hundreds of gigawatts of clean energy is leveraged, the country could see a rapid increase in renewable capacity and greater economic growth.

Northeast Asia Power System Interconnection

Located next to energy mammoths like China and Russia, and in close proximity to Japan and Korea, Mongolia could be a clean energy exporter to neighboring countries. The project known as the Northeast Asia Power System Interconnection (Napsi) aims to develop an interconnector between Mongolia and various countries in northern Asia to ensure markets can meet the growing demand for clean energy. Mongolia’s vast land and high-quality natural resources could host up to 192GW of wind and 1,166GW of solar capacity in the southern region in close proximity to China, according to a study undertaken by the Asian Development Bank.

Though the idea of an Asian SuperGrid has been discussed for over a decade, the project is still in the early conceptual stages, and feasibility studies are still being undertaken. Progress has been slow as any power exports from Mongolia will have to go through Russia or China to reach Korea and Japan, which will not be feasible until geopolitical issues have been resolved. Beyond geopolitical challenges, the distance involved in this project could range from 1,500 to 3,000 kilometers, adding to the upfront cost and complexity. Far more international policy coordination, as well as significant amounts of funding and planning, will be required to see this project come to fruition. If however, it does go ahead, it could pose big opportunities for Mongolia’s clean energy system.

Hydrogen

If Mongolia can get its renewable energy sector momentum back up and running, it has ample land and natural resources to support a green hydrogen industry. Smaller groups and independent players, like the Mongolian Hydrogen Council, are looking into this potential and garnering interest from international buyers.

Elixir Energy, an Australian gas exploration company, has signed a memorandum of understanding with the Mongolian Energy Ministry to investigate opportunities to create a hydrogen industry in Mongolia. The company sees potential in the South Gobi region, which boasts high wind speeds and lots of sunshine, making it a perfect region for hydrogen electrolyzers.

Yet the country currently sees no government policy, target or support for the nascent hydrogen sector. Globally, clean hydrogen production is rising, and could rise 30-fold by 2030, according to BNEF. However, demand remains low; at the moment, only 12% of hydrogen production capacity has a potential buyer. That means Mongolia will be up against stiff competition for selling any hydrogen it does produce, and having firm offtake agreements in place will be key for the success of the sector.

NetZero Pathfinders

For more information on best practices and climate action, explore the NetZero Pathfinders project by BloombergNEF.