A hydro heavy hitter turns its eyes toward solar.

With more than 90% of its power from hydro, Albania is looking to become a Balkan solar powerhouse.

With over 90% of its energy from hydroelectric power, Albania already enjoys a largely clean energy mix. Now it has an opportunity to become an Eastern European solar powerhouse. To do so, it will need to address an array of regulatory concerns – with a particular focus on speeding up land regulation reform, consolidating its grid structure and boosting private sector engagement.

-

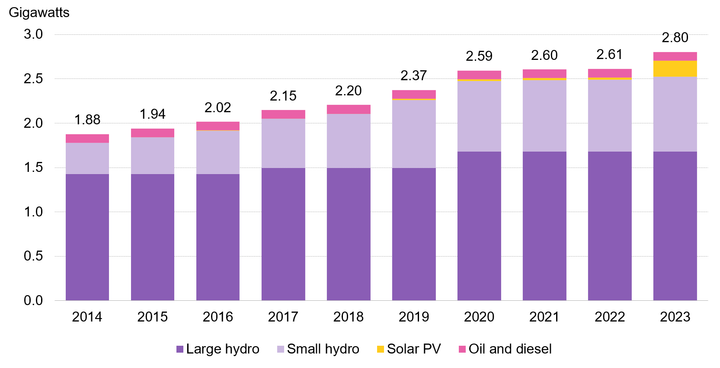

Albania has an installed capacity of 2.8 gigawatts, 40% of which is from renewable energy sources excluding large hydro. If large hydro is included, then the share jumps to 96%.

-

Solar capacity is expected to grow significantly in the next few years. Not only is Albania one of the sunniest countries in the region, with around 2,400-2,500 hours of sunshine per year, but it has also effectively implemented a renewable energy auction program that is set to drive growth in utility-scale solar plants. In October 2023, the largest solar power plant in the western Balkans, the 140-megawatt Karavasta plant, became operational in southern Albania, marking the beginning of a series of solar projects that are set to come online in the country by the end of the decade.

-

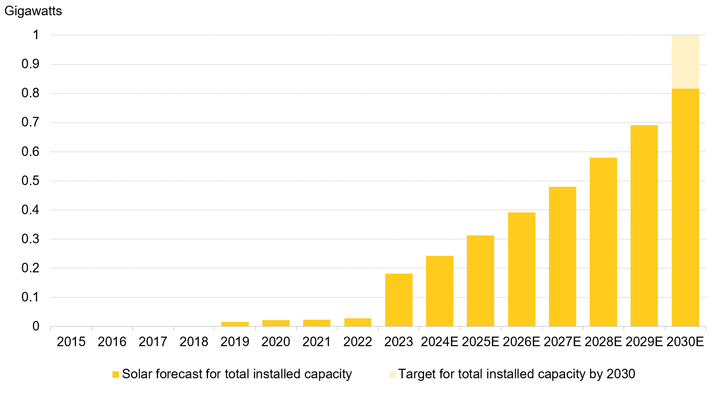

BloombergNEF estimates that Albania could add 800 megawatts of solar by 2030 – bringing total installed solar capacity to 29 times what it was in 2022. Almost $200 million was invested in Albanian solar projects last year. Yet even this dramatic growth rate falls short of the country’s 1 gigawatt of solar by 2030 target.

-

A new law passed in April 2023 established an ambitious renewable energy target, and renewable energy auctions in Albania are thriving. In the six years since these auctions were introduced, they have delivered some of the lowest prices seen in the western Balkans.

-

The April 2023 law also includes specific regulations for the promotion of wind and photovoltaic projects, but there is a lack of clarity in terms of renewable energy investment and private sector participation.

Figure 1: Albania’s installed capacity, by technology

Source: BloombergNEF

1. Power

1.1. Power policy

Albania first established a renewable energy target in 2016. Part of the EU’s National Renewable Energy Action Plan (NREAP), it aimed to have renewable energy account for 38% of the country’s total final consumption by 2020. Albania achieved its first target in time, and a new target of 42% renewable energy in total final consumption by 2030 was introduced in the 2021 National Energy and Climate Plan (NECP).

In April 2023, the country went one step further, when the Albanian Parliament passed Law 24/2023 on the “Promotion of the use of energy from renewable sources”. This included the most ambitious target yet: 54.4% of renewable energy in gross final consumption by 2030. This is considerably higher than the binding EU target of 42.5% renewable energy in final consumption, which was adopted in September 2023.

In addition to clear and binding targets, Albania’s supportive policy mechanisms have built a thriving renewables market with renewable energy auctions seeing record-low prices in the western Balkans in the six years since they were first implemented. The first auction, held in August 2018, for a 50-megawatt (MW) solar photovoltaic (PV) plant, was set at €0.0599/kilowatt-hour ($0.0635/kWh) over 15 years. That’s lower than the base prices at the Hungarian Power Exchange (HUPX), the reference for the electricity import price in the region, registered in August and September of the same year.

Another four rounds have been held since then (in 2020, 2021, 2023 and 2024). All except the 2023 round were for solar projects; the 2023 round, which was specifically for onshore wind, brought in bids ranging from €0.0448/kWh to €0.0749/kWh. In April 2023, the Ministry of Energy announced plans to install 1 gigawatt (GW) of solar capacity by 2030 “through clean, transparent and competitive procedures.”

The latest round, which ended in July 2024, introduced a new criterion: investors are now obligated to secure land rights themselves. That could prove to a significant hurdle, since Albania lacks clarity in this matter, as land reform – and specifically property rights – have not been effectively implemented since the end of the Soviet Union.

Small hydro, solar and wind energy projects in the country have benefited from feed-in tariffs and import tax exemptions since 2014, but value-added tax (VAT) exemptions, which were introduced in the same year, only apply to solar PV and wind machinery, and do not pertain to hydro related equipment. Albania’s net-metering policy, first introduced in Law No 7/2017 Article 15, only went into effect in 2019, and it applies to family households, as well as small- and medium-sized enterprises generating up to 500 kilowatts (kW) of power.

1.2. Solar

Albania’s solar sector is expected to grow significantly in the next few years, thanks to its sunny weather and an array of supportive policies. BNEF estimates up to 800MW in solar will be added by 2030 – 29 times the 28MW of solar capacity installed in 2022. Yet even with that huge growth rate, Albania would still fall short of its target of 1GW of solar by 2030.

Figure 2: Albania’s installed solar capacity, historical and forecast

Source: BloombergNEF. Note: Solar here refers to solar photovoltaic.

On the investment front, Albania’s solar sector attracted $286.2 million over the last 10 years, although $192.2 million of that sum poured into the country in 2023 alone. Multiple local and foreign firms have been interested in developing solar and wind projects in Albania, including the Turkish company Fortis Energy, which has a 639MW portfolio of projects for these two technologies in the country.

1.3. Wind

While there is considerable wind potential in the country. The most promising sites, such as the Lezhe mountains, are along the Adriatic coastline. Yet this technology is unlikely to compete with solar in the coming years. BNEF estimates wind will reach 370MW of installed capacity by 2030 – less than half of forecast solar build – based on the projects currently in the pipeline.

Three projects won the first wind auction round in 2023, but so far, no capacity has been deployed, as the sector has faced challenges in securing permits and establishing projects’ financial viability. For instance, in 2020, the Albanian Energy Regulatory Authority set the price of power from wind farms of up to 3MW at around €76 per megawatt-hour ($83/MWh), while hydro plants of up to 15MW see prices at €50/MWh.

2. Power prices

Albania is among the western Balkan countries with the highest electricity prices. Even with a high share of power being generated by hydroelectric power plants, Albania must still import a third of its electricity in order to meet demand. Since 2014, households pay 9.5 lek per kilowatt-hour ($0.11/kWh), and businesses pay 14 lek.

The country has faced a high level of energy poverty for a long time, meaning many inhabitants lack sustained access to electricity, clean cooking facilities and other basic energy needs. While the 2021 Albanian NECP recognizes energy poverty as a priority and in need of a systematic monitoring approach, the national plan also recognizes that “there are no specific policies to address the energy poverty.” If power prices increase too rapidly, there are direct financial compensation mechanisms in place for low-income households (within the threshold of 200-300kWh/month), in addition to other forms of power subsidies. Even so, low-income households still struggled to pay their electricity bills in 2022, as spiking gas prices caused by Russia’s war in Ukraine directly affected the overall price of electricity in the country.

3. Power market

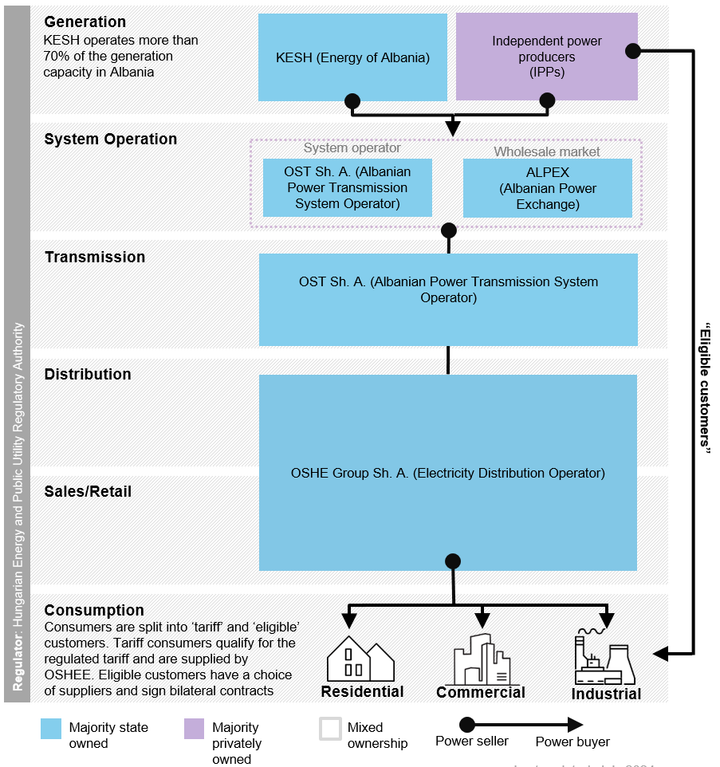

Albania’s power sector is unbundled but dominated by state-owned entities including the Albanian Electricity Corporation (KESH), the Transmission System Operator (OST) and the Distribution System Operator (Oshee). There is limited private sector participation in the generation sector, and no form of standardized power purchase agreement (PPA).

Over the last decade, the process of unbundling and liberalizing the sector has faced a series of hurdles. In January 2018, the Energy Community Secretariat opened a dispute settlement case against the country, due to the delayed and incomplete unbundling of Oshee, which was first introduced in Law 43/2015. Just a few months later, in April 2018, Oshee said it had successfully concluded the process, as the utility was broken down into three different entities. Nonetheless, the Secretariat argued that this was simply a functional unbundling, as the entities were not fully legally independent from each other. The case was finally closed in 2023, after the legal unbundling of the three state-run companies was finalized.

In the same year, Albania’s Power Exchange (Alpex) was officially launched when it held its first day-ahead auction in April 2023. This is a joint venture owned by the transmission system operators of Albania (OST) and Kosovo (KOSTT), operating day-ahead and intraday markets in Albania and Kosovo. Even though this shows progress in the country’s power-market liberalization, Alpex has been operating with limited liquidity, as only the transmission losses and the volumes for the supplier of last resort are traded at the power exchange. This is viewed as a significant short-term challenge, as lack of liquidity limits the volume of international trading.

Figure 3: Albania’s power market structure

Source: BloombergNEF.

4. Barriers

Key barriers to the development of renewable energy projects in Albania are the delayed implementation of laws and the lack of the grid infrastructure needed to streamline its energy transition.

For example, there has been no progress in the implementation of the “Decision on the Approval of Practices for the Promotion of Joint, Regional Investment in the Energy Infrastructure”. This was adopted in 2018, and it follows EU Regulation 347/2013, since Albania must follow the EU’s rules. The decision obligates the national competent authority to define and publish the manual of procedures, and to annually inform the Electricity and Gas Working Groups of the Energy Community, including the Secretariat, about the realization and status of Albanian regional Projects of Energy Community Interest (PECI).

Lastly, the country’s dependency on large hydro makes it difficult for other technologies to be introduced in the energy mix. While this is slowly changing – solar projects accounted for 5.6GW of the 10.5GW of grid connection requests in 2023 – only two contracts were signed by the OST. In the coming years, Albania will need to find ways to effectively implement the projects in its pipeline if it is to reach its 2030 renewable energy target.

NetZero Pathfinders

For more information on best practices and climate action, explore the NetZero Pathfinders project by BloombergNEF.